Course Design

Whether designing a new course or preparing to adopt a standardised curriculum, the instructor will find it helpful to begin the course preparation by asking key questions such as:

- “What do I want my students to learn?”

- “How do I measure my students' learning?”

- “How will my students learn?”

The most common approach to course design focuses on creating and/or selecting a list of content that will be taught. However, Wiggins and McTighe (1998) argues that “only when one knows exactly what one wants students to learn should the focus turn toward consideration of the best methods for teaching the content, and meeting those learning goals”. They propose the “Backward Design” framework for course design. This framework is “backward” only to the extent that it reverses the typical approach, so that the primary focus of course design becomes the desired course learning objectives.

Backward Design is beneficial to instructors because it innately encourages intentionality during the design process. The instructor is required to focus on (1) successful student outcomes by determining measurable course learning objectives and then (2) determining assessments that will assist the instructor in determining if the students have met the learning objectives. After the assessment methods have been determined, the instructor works backward to (3) plan ways to deliver the content (i.e. instructional strategies) that will lead the students toward successful completion of the assessment.

Good course design does not happen by chance. Designing a course takes extensive planning and using the Backward Design framework, in combination with an understanding of research-based, effective principles of how students learn can help an instructor design an effective course. This webpage provides you with self-help instructions on how you can apply the principles of Backward Design to develop your course outline. The assessment methods and instructional strategies are organized according to the Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy thinking levels.

3 Stages of the Backward Design Framework

Click on each section to learn more details on the 3 stages of the backward design framework.

Building your Course: How do I get Started?

Start with the end in mind

Start by your getting hands on a course outline template (click here for a sample). You can contact your school manager, course coordinator, area coordinator or relevant programme director to have a course outline template specific to your school. Although there may be slight variations in what is required for different schools, all course outlines typically start with a description of the course, and its intended learning outcomes. At this stage, you define:

- The course description

- The course learning objectives, i.e. what students should know, understand and be able to do by the end of the course

CTE recommendation: Writing measurable learning objectives

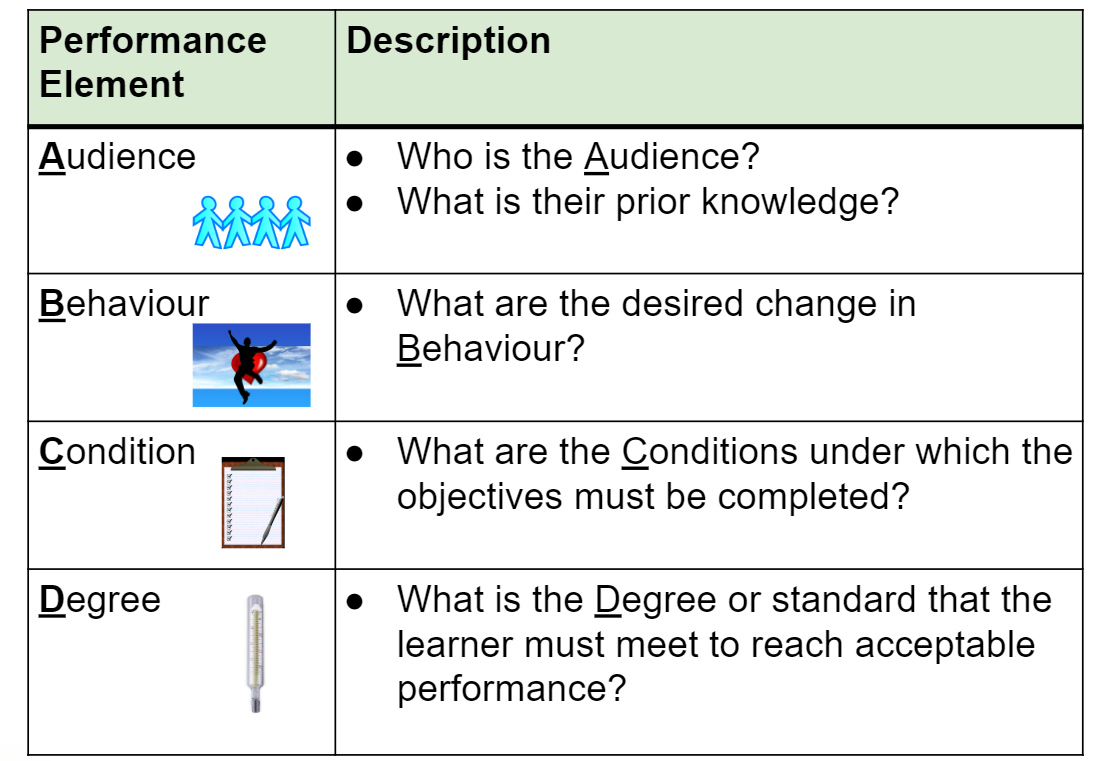

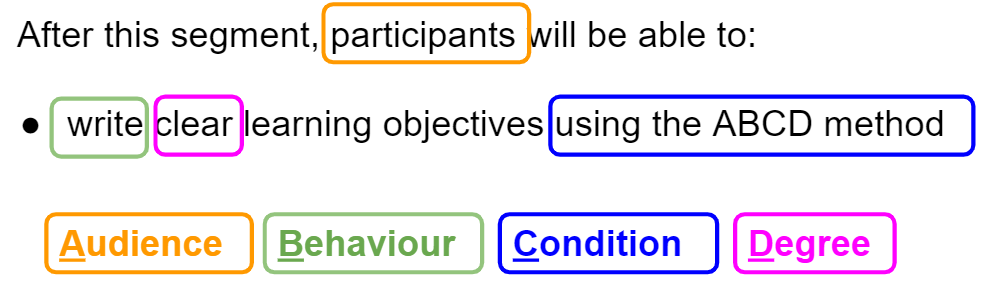

A clear and measurable learning objective has four distinct performance elements: Audience, Behavior, Condition and Degree (ABCD) (Smaldino, Lowther & Russell, 2007). This is a good starting point on coming up with measurable learning objectives.

Figure 1. ABCD model for writing learning objectives

Figure 2. Example of a learning objective written using the ABCD model

Biggs and Tang (2011) recommend having no more than five or six intended learning objectives, for a semester-long course. A set of five or six well-crafted course learning objectives communicates a holistic overview of the course. Any more than five or six course learning objectives will make it difficult for the instructor to align his/her teaching and learning activities and assessment tasks to each (p. 119).

The Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001) provides a useful resource on the action verbs for writing learning objective in specific and measurable language. Once you have the learning objectives articulated, you will find it easier to align your assessment methods (Table 2) and instructional strategies (Table 3).

Table 1. Thinking Levels of the Bloom's’ Revised Taxonomy1

|

Thinking Level |

Description Action Verbs |

|---|---|

|

Remember |

Recognising or recalling knowledge, facts or concepts. Verbs: define, describe, identify, know, label, list, match, name, outline, recall, recognise, reproduce, select, state, locate |

|

Understand |

Constructing meaning from instructional messages. Verbs: illustrate, defend, compare, distinguish, estimate, explain, classify, generalise, interpret, paraphrase, predict, rewrite, summarise, translate |

|

Apply |

Using ideas and concepts to solve problems. Verbs: implement, organise, dramatise, solve, construct, demonstrate, discover, manipulate, modify, operate, predict, prepare, produce, relate, show, solve, choose |

|

Analyse |

Breaking something down into components, seeing relationships and an overall structure. Verbs: analyse, break down, compare, select, contrast, deconstruct, discriminate, distinguishes, identify, outline |

|

Evaluate |

Making judgments based on criteria and standards. Verbs: rank, assess, monitor, check, test, judge |

|

Create |

Reorganise diverse elements to form a new pattern or structure. Verbs: generate, plan, compose, develop, create, invent, organise, construct, produce, compile, design, devise |

1 Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D.R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing, Abridged Edition. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Put into practice: Completing your course outline document

|

Course Description

*The graduate learning outcomes refer to the university-wide highest learning goals that are important for all undergraduates. |

| Learning Objectives Learning objectives are specific statements about the key knowledge and skills that students will acquire after completing your course. They should be observable and measurable such that students are able to demonstrate and that you can assess. Craft learning objectives using the list of action verbs from the Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy (Table 1) and present them as follows: By the end of the course, students should be able to:

|

Decide Ways to Collect Evidence of Student Learning

At this stage, you determine:

- The different assessment methods that demonstrate students’ achievement on the course learning objectives and their respective weightages/weightings towards the course grade

- Whether you would assess students formatively (i.e. student is expected to learn from provided feedback) and/or summatively (i.e. grade awarded contributes to the overall grade at the end of the course)

- The criteria (i.e. rubrics) you will use to ensure consistency in your evaluation of your students’ work (Click here for samples of grading templates contributed by SMU instructors)

CTE recommendations:

- Plan assessments at the time the course outline is initially developed

Often, learning objectives are framed in advance of the assessment plan. Then, when the assessment plan is being developed and it becomes clear that the learning outcomes were framed poorly, instructors may end up with a situation of misalignment between the two. We recommend that you plan your assessments at the time the course outline is initially developed such that the learning objectives can be seen to be assessed and achievable within the timeframe of the course.

- Select appropriate assessment methods to measure your course learning objectives

Some assessment methods are more suitable for assessing student learning at each thinking level of the Bloom’s revised Taxonomy. Table 2 provides a reference help you select the most appropriate assessment methods to measure your course learning objectives. In the instance where an assessment method can be used for assessing more than one thinking level, it will be mapped to the highest possible thinking level.

In judging whether students have met the learning outcomes, consider creating a rubric to make this transparent to students and to ensure consistency in your evaluation of students’ work. Our faculty members have given CTE permission to share their rubric templates with the SMU community. The grading templates can be accessed here. Please feel free to adapt the rubric templates according to your course. Click here for a resource guide on how to create quizzes in eLearn.

- Using tools to assess and provide feedback for group assignments

For group assignments or projects, instructors can consider using the Peer and Self Feedback System (PSFS) on eLearn to monitor and provide feedback on individual students’ contributions. The survey includes standardised sets of descriptors for students to evaluate their peers. If the instructor prefers to customise questions for students to evaluate their peers, they may use the Peer Evaluation Tool (PET) instead.

It is advisable for instructors to inform students about how the feedback from peers will impact their final overall score for the group assignments or project before the tasks begin. For example, one instructor allocates 2 out of 10 “class participation” points for completing the peer evaluation with thoughtful comments and proportionally deducts points from the 5-point “group contribution” marks if the average peer evaluation score across all questions is less than 3 out of 6 in a customized scale.

Instructors should specify these weightage details in the Assessment Method section of their course outlines and communicate them during class time. This transparency ensures students take the peer evaluation process seriously. Click here to find out more about the PSFS and the PET.

Put into practice: Completing your course outline document

|

Assessment Methods

An example is as follows:

|

Crafting Questions

Selected Response Questions

Examples of selected response assessment items (also referred to as objective assessments) include multiple-choice questions (MCQs) and true/false questions. In crafting effective short response items, construct questions that target higher-order thinking (HOT) skills (consistent with the application, analysis, and synthesis levels of Bloom’s taxonomy).

Crafting Effective MCQs

Effective MCQs require more than just simple memorisation of facts. Bloom’s taxonomy provides a good structure to assist instructors in crafting MCQs. MCQs can therefore be divided into two levels, i.e. lower level cognitive questions which assesses knowledge, comprehension and application and higher level cognitive questions, which assesses application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Classroom assessments should demand both lower-order thinking (LOT) and HOT skills. MCQs can address HOT skills by including items that focus on understanding (“how” and “why” questions). Therefore, MCQs that involve scenarios, case studies and analogies can be crafted such that students are required to apply, analyse, synthesise, and evaluate information. There are many pros and cons of using MCQs and this is addressed in the paper by Simkin and Kuchler (2005).

Here are a few links to examples of MCQs using Bloom’s Taxonomy:

- Testing Programming Skills with Multiple Choice Questions

- Here is an example of MCQs using Bloom’s Taxonomy from the University of Canberra.

Constructed Response Questions

Constructed response assessments are written assessments which include short response items (e.g. fill-in-the-blank questions) or extended response items (e.g. short or long essays).

When crafting short response questions, keep it focused to ensure that the question is clear and that it has a definitive answer. For example, a short response might ask a student to “illustrate a concept with an example” or “compare and contrast two or more concepts.”

Effective extended response assessment such as essay questions require students to use higher-order cognitive level thinking skills, by requiring them to organize, interpret and integrate information, assess and evaluate ideas and provide convincing arguments and explanations to support their opinions.

Essay questions are extended constructed response assessments where the student is required to respond to a general question or proposition in writing. This type of assessment allows students to demonstrate their reasoning related to a topic, and as such, demand the use of higher level thinking skills, such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

Studies in the literature have acknowledged the potential of using essays to assess higher levels of student understanding and suggests several guidelines to make essays more reliable for measuring the depth of understanding. Well-written crafted essay questions should specify how the students should respond and should provide clear information about the value/weight of the question and how it will be scored (please see section on the use of assessment rubrics).

Here is a link to examples of preparing effective essay questions.

Using Rubrics

Using rubrics for feedback and learning

A rubric is considered as a scoring tool that lays out the specific expectations for a task / assignment. It divides the task / assignment into its component parts and provide a detailed description of what constitutes acceptable or unacceptable levels of performance for each of the parts.

A rubric helps to ensure that the assessment of student learning matches with the desired learning objectives. It also ensures that there is some level of agreement among different raters/assessors.

Here are the steps to help you design and build a rubric:

- Identify the criteria for assessment by referring to the learning objectives that were specified during the design stage.

- For each criterion identified, decide how it can be observed or measured. Specify the attributes that students are expected to show in their work.

- Based on the attributes specified above, identify the characteristics or traits that qualify as “exceeding expectations (good)”, “meeting expectations (average) or “below expectations (low)”. If a 3-level rating scheme is not sufficient, more intermediate levels can be considered.

- Express the characteristics or traits as detailed descriptors for each level of performance by using precise words to explain how the characteristics or traits can be observed or measured.

To illustrate, the table below shows sample rubric for an essay writing-type of assessment method, where students are expected to arrive at a plausible solution for a business problem. There are eight criteria in the rubric to assess students on the learning objectives and there are three levels in the rating scheme (low, average and good). The items in each cell explain the different attributes to qualify for each level of rating.

|

Criterion |

Level 1 |

Level 2 |

Level 3 |

Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Identifying the problem |

Not able to correctly identify the problem |

Able to correctly identify the problem without providing details about the situation |

Able to correctly identify the problem and provides details about the situation |

|

|

Analysing the pertinent issues |

Able to list and analyse only some of the pertinent issues and lacks in-depth analysis |

Able to list and analyse all the pertinent issues but lacks in-depth analysis |

Able to list and analyse all the pertinent issues in depth |

|

|

Presenting a list of alternatives |

Able to identify only one or two alternatives |

Able to identify a list of alternatives but fails to provide details for all the alternatives |

Able to identify a list of alternatives and provides details for each |

|

|

Comparing and contrasting the alternatives |

Able to list the pros and cons of only some alternatives and fails to weigh them against one another |

Able to list the pros and cons of all the alternatives but fails to weigh them against one another |

Able to list the pros and cons of all alternatives and weighs them against one another |

|

|

Providing a plausible solution |

Not able to provide a plausible solution and makes no attempts to justify the decision |

Able to provide a plausible solution but provides little justification |

Able to provide a plausible solution with good justifications |

|

|

Structure of the essay |

Not structured and materials are disconnected |

Well-structured but materials are not well connected |

Well-structured and materials are presented in a coherent manner, with good linkages |

|

|

Grammar |

Full of errors in grammar, punctuation or spelling |

Contains some errors in grammar, punctuation or spelling |

Free of errors in grammar, punctuation and spelling |

Rubrics can be used either for formative (to give feedback and learning) or summative (for evaluation and grading) purposes. To use rubrics for formative purpose, first allocate a rating in each criterion for each level (say a numeric one for Level 1 and two for Level 2). Next, award a rating for each student and take the average score for rating of all students for each criterion. This average score will provide instructors with information on the areas of strengths and weaknesses of the students across the criteria.

The criteria address the learning objectives of the course, so naturally, if the assessment data shows that students have not accomplished certain learning objectives in the course, instructors can decide how to fine-tune their instructional strategies, in accordance to the learning objectives set in the course. Instructors may also decide how to refine the course learning objectives, if appropriate, and make them more transparent to the students. Or, instructors may decide to redesign the course assessment so as to address the course learning objectives. Through such a systematic feedback loop, rubrics are therefore, useful for giving feedback to students on how to improve their learning, as well as giving feedback to instructors how to refine their teaching. One can then assure that there is structure and proper alignment in the way the course is designed.

The rubric should be constantly reviewed and revised for improvements as they are being used to ensure that they are adequate and appropriate for use for different groups of students, who have varying backgrounds and abilities. Where possible, instructors should pilot-test the rubrics on students’ assignments so that they can identify deficiencies or unsuitability in using the rubric.

Using Rubrics for Evaluation and Grading

More often the case, rubrics are used for the purpose of evaluating and grading students’ assignments. For this purpose, marks are allocated for each criterion to indicate the weight of it in the overall grading scheme and a range of marks for each level of performance is determined.

The table below shows a sample grading rubric for the abovementioned essay writing-type of assignment. The marks add up to 100 in total, with a greater percentage of the marks for the content-specific cognitive skills than that for writing skills. The marks are summed up for every student and the total marks for the students would reflect their grade for the writing assignment.

|

Criterion |

Level 1 |

Level 2 |

Level 3 |

Average Rating

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Identifying the problem |

Not able to correctly identify the problem |

Able to correctly identify the problem without providing details about the situation |

Able to correctly identify the problem and provides details about the situation |

|

|

Analysing the pertinent issues |

Able to list and analyse only some of the pertinent issues and lacks in-depth analysis |

Able to list and analyse all the pertinent issues but lacks in-depth analysis |

Able to list and analyse all the pertinent issues in depth |

|

|

Presenting a list of alternatives |

Able to identify only one or two alternatives |

Able to identify a list of alternatives but fails to provide details for all the alternatives |

Able to identify a list of alternatives and provides details for each |

|

|

Comparing and contrasting the alternatives |

Able to list the pros and cons of only some alternatives and fails to weigh them against one another |

Able to list the pros and cons of all the alternatives but fails to weigh them against one another |

Able to list the pros and cons of all alternatives and weighs them against one another |

|

|

Providing a plausible solution |

Not able to provide a plausible solution and makes no attempts to justify the decision |

Able to provide a plausible solution but provides little justification |

Able to provide a plausible solution with good justifications |

|

|

Structure of the essay |

Not structured and materials are disconnected |

Well-structured but materials are not well connected |

Well-structured and materials are presented in a coherent manner, with good linkages |

|

|

Grammar |

Full of errors in grammar, punctuation or spelling |

Contains some errors in grammar, punctuation or spelling |

Free of errors in grammar, punctuation and spelling |

|

|

Total marks: |

For instructors, the rubric provides the characteristics for each level of performance on which they should base their judgment on. For students, the rubric provides clear information about what they are expected to deliver against certain benchmarks.

Indeed, the marks for each criterion reflect the importance of the criterion in the instructor’s grading scheme. For example, using the sample above, the weight allocated to the criterion “Comparing and contrasting the alternatives” is relatively high compared to the other criteria, and this indicates the importance of this criterion in the instructor’s grading scheme. In comparison, the weight allocated to the criteria “Structure of the essay” and “Grammar” are relatively lower and this indicates a lower level of emphasis put on writing skills. Overall, the design of the rubric suggests that the instructor has greater emphasis on the content–specific cognitive skills, in proper alignment to the learning objectives he/she has set for the course.

Some instructors may also want to allocate a certain percentage, such as 5-10% of the total marks as discretionary bonus points to reward students for work done above and beyond the required norms dictated by the instructor. Doing so gives students the creativity and flexibility to explore beyond the criteria defined by the instructor and get rewarded for putting in additional efforts to enhance the standard of their work.

Technically speaking, when rubrics are used for grading purposes, the students’ overall grades do not constitute an assessment for learning. This is because different students who attain the same grade may have strengths and weaknesses in different areas (and the weighting of each criterion would further magnify this effect).

The websites of Kathy Schrock (link) and Carnegie Mellon University (link) are also useful resources on rubrics for assessment.

Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction

At this stage, you consider:

- The instructional methods/strategies that you will use to guide the learning so as to get students ready to tackle the assessments you planned for

- The resource materials, i.e. recommended text and readings

- The sequence of your lessons, i.e. the Weekly Lesson Plan

CTE recommendations:

- Increasing students’ cognitive engagement through active learning approaches

The ICAP framework researched extensively and proposed by Michelene Chi and Ruth Wylie (2014)1 , states that students’ overt behaviors when engaging in active learning approaches can be categorized into passive, active, constructive and interactive modes, where I>C>A>P, with the Interactive mode of engagement achieving the greatest level of student learning. We recommend that you include learning activities at the constructive and interactive modes whenever possible in your instructional strategies. You can find some suggestions on how to implement the ICAP framework for each of the instructional strategies in Table 3.

- Selecting instructional strategies that prepare students for the assessments that you planned

Depending on the level of thinking you require your students to demonstrate in your learning objective and assessment, your instructional strategies should provide opportunities for relevant practice and feedback. Bloom's Revised Taxonomy (Table 1) offers one framework to understand the different levels of thinking and Table 3 lists some recommended instructional strategies corresponding to each level.

Putting into practice: Completing your course outline document

Instructional Methods/Strategies

Describe the ways in which you will deliver the course, and the key instructional activities that your students need to do in order to achieve the learning outcomes. Strive for interactivity in the way you deliver your course to be better aligned to SMU’s pedagogy.

Expectations

Expectations are desired behaviors or outcomes of students. Stating your expectations upfront on what you want students to complete prior to coming to class (e.g. homework assignments, pre-readings) and expected classroom behaviour (e.g. punctuality, attendance, laptop/handphone usage) can help you greatly in managing your students.

An example is as follows:

| Instructional Method / Strategy | Description (Purpose / Format) | Expectation(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Group Presentation |

Purpose: The purpose of the group presentation is for you to share your research findings on an area that you are interested in, related to international financial market. Format: Each group will be given 20 minutes to present, followed by 10 minutes for Q&A. The instructor will probe and question you during the presentation so as to assess your ability to reason critically in areas that cannot be assessed by written exam, e.g. oral communication skills, conciseness, persuasiveness, quality and clarity of responses to questions, body language and professional manner. |

You will be expected to work collaboratively and contribute actively towards the group presentations. You will be assessed by the instructor and your peers of your contributions. |

Recommended Text and Readings

E.g.: Book title, edition, year of publication; Author(s); Publisher: ISBN number of available

Consultations

State your consultation hours and mode(s) (e.g. online and/or face-to-face), and the minimum work efforts expected from your students before they come for their consultation sessions with you.

Bibliography

- Wiggins, Grant, and McTighe, Jay. (1998). Backward Design. In Understanding by Design (pp. 13-34). ASCD.

- Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. Allyn & Bacon.

- Biggs, J., Tang, C., & Society for Research into Higher Education. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University : What the Student Does , Philadelphia, Pa. : McGraw-Hill/Society for Research into Higher Education ; Maidenhead, Berkshire, England ; New York : Open University Press. (Available for loan from SMU Libraries)

- Smaldino, S. , Lowther, D. and Russell, J. (2007) Instructional Media and Technologies for Learning, 9th Edition. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, Inc.

- Begum, T. T. (2012). A Guideline on Developing Effective Multiple Choice Questions and Construction of Single Best Answer format. Journal Of Bangladesh College Of Physicians Surgeons, 30(3), 159-166.

- Reiner, C. M., Bothell, T. W., Sudweeks, R. R., & Wood, B. (2002). Preparing Effective Essay Questions.

- Simkin, M. G., & Kuechler, W. L. (2005). Multiple-Choice Tests and Student Understanding: What Is the Connection?. Decision Sciences Journal Of Innovative Education, 3(1), 73-97.

- Walstad, W. B. (2006). Testing for Depth of Understanding in Economics Using Essay Questions. Journal Of Economic Education, 37(1), 38-47.

- Schrock, K. (2012). Assessment and Rubrics. Retrieved from http://www.schrockguide.net/assessment-and-rubrics.html

- Carnegie Mellon University. (n.d.). Using rubrics to enhance online teaching and learning. Retrieved from https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/designteach/teach/rubrics.html